Time and Distributed Systems

Have you ever thought about how devices display the current time? I must confess I have always taken for granted that we have access to the current time. To this day, I have only been curious about how this process works once I started studying distributed systems. There's a fascinating story behind it!

Bear with me 😊

Time is a relative measurement, and its definition has changed over time. Humans started measuring time centuries ago, and it's been crucial for all civilizations, driving all technological advancements. Initially, humans observed the sky and determined the time of the day based on the moon and the sun's position. Devices such as sundials, water clocks, pendulums, sand clocks, etc., appeared. These evolutions were necessary because humans have required more time precision throughout time. There's a lot of history behind this; however, I am interested in analyzing this evolution from a technological perspective, more specifically, from a computational perspective.

Most ways we measured time would not be valuable today because those methods needed more precision. For example, observing the sun and moon's position isn't reliable because the earth's rotation speed is not constant (to my surprise). That rotation speed can be affected by external events such as earthquakes, for example. So, humans worked hard to get to the clocks that we use today. In a world where nanoseconds matter, we need systems that accurately determine time. For example, aircraft systems depend on real-time operations that must happen within a strict timeframe; therefore, they can't allow unpredictability. That's why they use low-level programming languages where you have more control of the operations, such as manual garbage collection. Nevertheless, we do not yet have a method to determine the time with 100% accuracy, but the error rate is very acceptable.

To illustrate that accuracy, the time loss in pendulum clocks reduced the time loss of their predecessors from 15 minutes a day to about a minute a week [1]. Determining the time accurately even took away human lives. In the old days, the world was trying to find a mechanism to measure the longitude at sea, so they relied on the fact that a day consists of 24 hours, which means a 15-degree rotation every hour. As a result, a lousy time precision could cost route deviations of ships that could either take more time to their destination or, in the worst case, it could lead to death situations like what happened with four Royal Navy ships in 1707, an incident most known as the Scilly naval disaster.

The first public time service used clock beats wired from the Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This fact is quite interesting since one of the problems a software engineer will never get away from is dealing with time zones. In 1884, there was a conference where countries determined that the world should have different time zones and agreed to have 24 time zones. If you ever wondered why the world established GMT as the reference time, it was for several reasons, including but not limited to:

- They had the renowned royal observatory, a leading center for astronomical research

- 72% of the world's commerce depended on sea charts that used Greenwich as the prime meridian

The transition from GTM to UTC happened in ... (guess when?) ... January 1, 1972. This date marked the time we use today when handling UTC timestamps (also defined as the number of seconds that have passed since January 1, 1972). Pretty cool how this is connected, isn't it?

At this point, it shouldn't be a surprise that even Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, and Stephen Hawking spent part of their days trying to understand how time worked 😅

The outcome of many scientists' research led to two primary types of clocks:

- Quartz Crystal Clocks

- Atomic Clocks

Scientists discovered a material called Quartz Crystal, which vibrates at a highly regular rate when excited by an electric current. As a result, it became the standard for computer clocks. Today, your Apple Watch and laptop are equipped with Quartz Crystal Clocks. On the other hand, we have the atomic clocks. These are distinct clocks, but their accuracy is tremendous. They are known as cesium-beam atomic clocks and have an accuracy better than one nanosecond a day. But why don't devices use atomic clocks? Well, first of all, let's take a look at one:

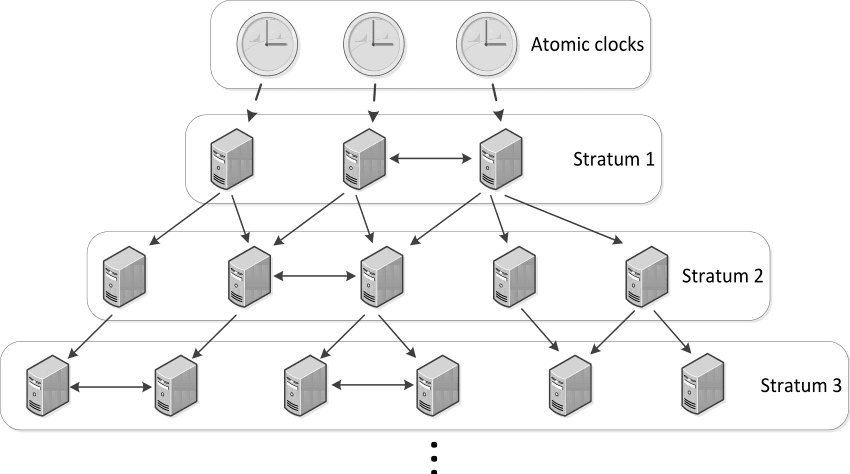

It's enormous and costly. The price varies depending on several factors, but this one, in particular, costs approximately $30K!!! To overcome this limitation, somebody came up with the idea of creating some sort of time synchronization using the best and most reliable distributed system in the world: The Internet! Each device runs an NTP server, which stands for Network Time Protocol, and there's a network of devices categorized into something called Stratum. Each device comes with a Quartz Crystal clock. Then it synchronizes with a server that is synchronized with another server that is synchronized with another server, etc., and at the end, it reaches a server that gets its time from an atomic clock. The network comprises 16 Stratum layers, and these atomic clocks usually live in satellites in space. This image illustrates what I'm saying:

Credits: https://substackcdn.com

Credits: https://substackcdn.com

You've probably tried to configure your computer's date and time. Usually, you can choose between two options: manual or automatic synchronization. When you select automatic synchronization, you have to choose a server. Apple computers connect to time.apple.com, but you can connect to a Google server or any other server in the Stratum network. When you select manual synchronization, you can set an arbitrary date. However, some applications perform security checks and will only allow you to use them if you have set the right time (Google Chrome, for example).

Ever since I became aware of this process, my mind spirals every time I look at the time on my computer.

In the last part of this post, we'll address the question: Why is this context important for computer networks, servers, etc?

Well, it's clear that time is crucial for so many operations in our day-to-day:

- Databases have procedures that automatically compute the

created_atorupdated_attime upon certain operations. - Aircraft and their real-time operations.

- Financial systems working with transactions and the stock market.

- Distributed Systems receiving messages where the order of the operations matters.

- Logging systems.

- Observability systems computing how much time operations took.

- Asynchronous jobs that get executed at a particular time.

- ... and the list goes on

Moreover, engineers must be diligent when writing software that requires time manipulation. Let's use this code snippet as an example:

current_time = DateTime.utc_now() |> DateTime.to_unix(:millisecond)

# perform some operations

end_time = DateTime.utc_now() |> DateTime.to_unix(:millisecond)

total_time = end_time - start_timeDid you know that total_time could be negative? That should be something rare, but theoretically, it's possible.

The above-mentioned NTP servers could shift your clock backward or forward in time, causing this apparently naive and harmless operation to give you an unexpected result. Instead, you must use a monotonic time in your programming language. In elixir, it looks like this:

current_time = :erlang.monotonic_time(:millisecond)

# perform some operations

end_time = :erlang.monotonic_time(:millisecond)

total_time = end_time - start_timeThe monotonic time is the time measurement since the system was powered, so it's pretty standard that telemetry systems rely on monotonic times rather than the system's clock because of this risk.

In conclusion, time is pivotal in how distributed systems work because we live in a world of distributed systems. A wrong computation of the current time can have nefarious consequences in many industries, and it's essential to get it right. I hope you learned something today and enjoyed reading this blog post as much as I had fun understanding where time comes from.

References

- A chronicle of timekeeping, 2006, Andrewes. W, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-chronicle-of-timekeeping-2006-02

- Distributed systems lectures, 2020, Klepmann, M, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UEAMfLPZZhE&list=PLeKd45zvjcDFUEv_ohr_HdUFe97RItdiB

Credits:

Credits: